Startups in the 3rd sector: Learning from Sidekick School

I gave this talk at an event organised by the Innovation Unit exploring new approaches to change in the 3rd sector. If you’d like to ask me any questions about it, please tweet me @choosenick!

Hello there

I’m Nick Marsh. I’m a designer and friend of Jo Harringtons [The guy who organised the event]. You can follow me on twitter @choosenick. I’m now the head of design at a children's book company called Lost My Name.

I’m here to tell you about a programme I set up back in 2012 called Sidekick School. Jo and I both thought it would be interesting for you guys as it put forward some quite different ways of organising projects in the 3rd sector. It was a semi success, and in this talk I’ll tell you a bit about why that was, and give you some suggestions for how people like you might do it better if you did it again.

We set up this programme when I was design director at Sidekick Studios. Sidekick was a design and technology agency I worked at between 2010 and 2013. It was a small agency - around 20 people at peak - but it punched above its weight.

We specialised in building software products for companies. We focused on products - things people pay for or that generate their own value - rather than marketing sites or internal IT. This is an example - we built a mobile video app for Red Bull that made it really easy to film and sequence clips of skateboarding and BMX videos for their pro riders and fans in order for them to bring user generated content into their wider video ecosystem.

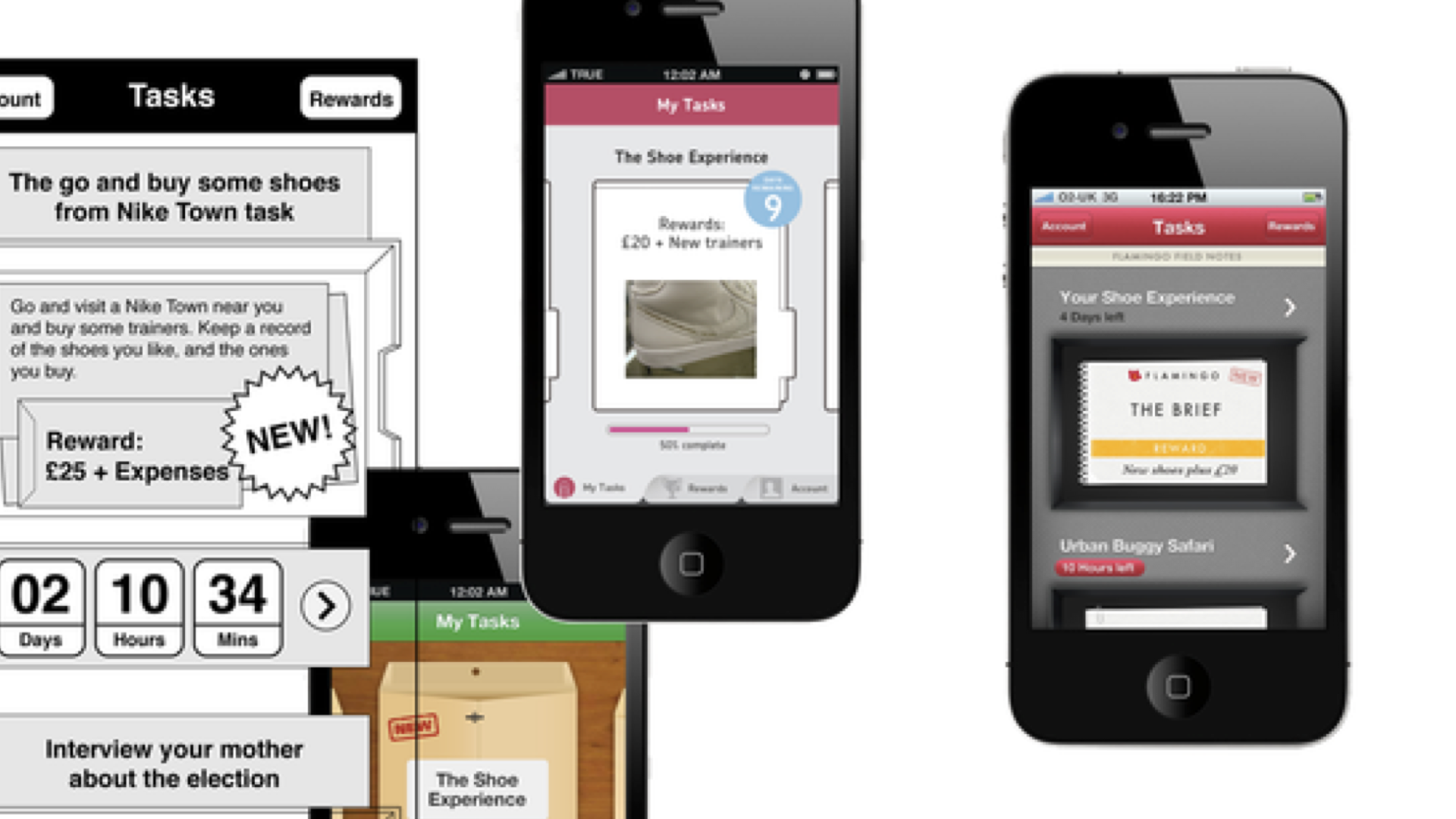

Or this - we made an app for a research company called Field Notes that made it possible to set tasks for respondents via their smart phones. Back in 2011 this was pretty big stuff. It turned into its own business unit and raised investment.

We positioned this work as ‘Startup as a Service’ - basically helping bigger companies act more like early stage companies. There were some common themes behind the projects we did. Normally we were helping the firms take advantage of a new technology (mobile was big then), use some data or capacity they had in a new way, or enter a parallel market. That sort of thing. To do this we generally setup a team of 3-4 people to work on a problem with them for around 3-6 months full time to launch a Minimum Viable Product - something that can test the hypothesis behind the business, in market.

At Sidekick we were very passionate about working with the 3rd sector and social businesses.

But they generally couldn’t afford this offering. Well that’s not true. It was more that they couldn’t take these kinds of risks.

So we had an idea - what if a deep pocketed funder could provide some of the funds so we could do this model for several charities at once, and de-risk the process for them, and us to an extent?

The funder would pay some of the costs, the charities would pay some and we would work at reduced rates (but do several projects). After a lot of searching we found a funder called Nominet Trust who backed us and we setup ‘Sidekick School’.

This was the basic process. Charities could apply via our website. They had to have a bit of an idea for a product or service that could make money and deliver on the social mission.

We’d then setup a chemistry meeting to discuss their ideas. If both parties wanted to move forward we put a product lead on the project and wrote a proposal with the charity. This took a few weeks normally.

If we went ahead we’d then do three months of product and customer development with them, with a view to trying to get a spin out.

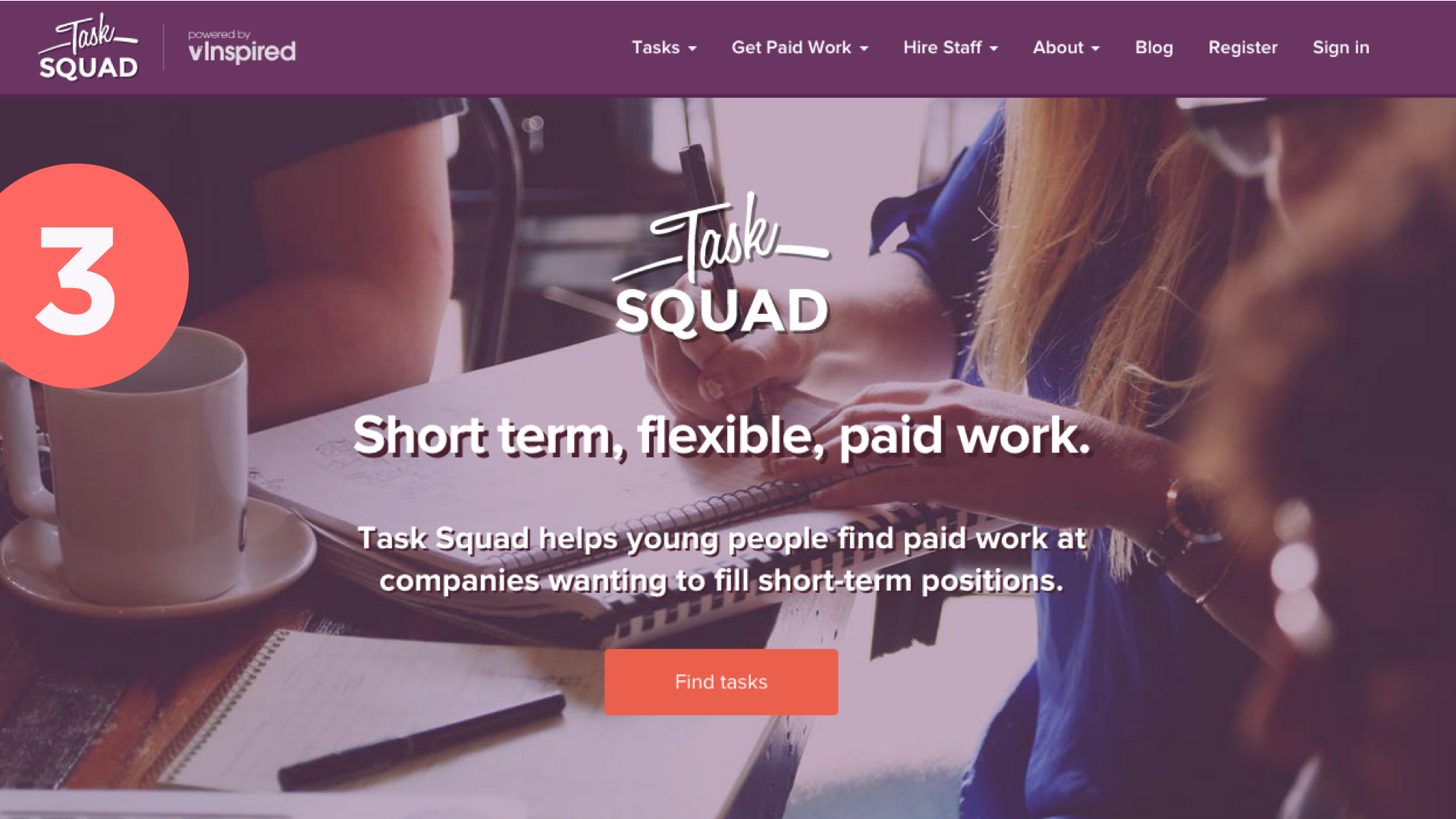

These were the basic ingredients of the projects:

- We’d put in £100k

- The charity would put in £50k

- We had to have the CEO sign it off so we knew it would get love

- They had to commit a full time product manager

- It had to be a Big Hairy Audacious Goal

These were some of the charities we worked up detailed proposals with that didn’t go through to production. They still got a lot from the process as we worked with them to create detailed pitches for new ideas.

So, the projects. We did four.

First, we made an app called Jointly for CarersUK. It’s a digital service designed to help people who care for other people manage their time and resources together. The business model is that it’s funded by an employers network that CarersUK has developed, and they offer this to their workforce to help reduce absenteeism. I think it’s still going.

Here’s another project we did. I don’t think his one made it. We built with with a small charity called Inaura. They were really too small and we shouldn’t have let them through, but they had a very passionate CEO that we loved.

It was called Narrative, and it was a tool for joining up care for kids who have been excluded from mainstream education. The idea was that schools would pay for it (as they have to pay for all the kids they exclude these days, apparently) and it came with lots of local services for the kids to take part in that cost less than sending them to a secure unit.

This was more successful and is still going strong. We built a service for Vinspired, the youth volunteering charity, that connected their existing pool of volunteers with paid work via a mobile app. It complemented their volunteering offer, and the business model was simple - employers pay! Genius.

Finally, we did an ambitious project for Comic Relief to explore how they could make money year round outside of their telethon. We did this by building six products in six weeks.

We built a stupid gambling game called Dare Roulette.

A video on demand service on top of their archive for schools called Topic Telly.

We built an app for runners to get sponsored for running all year round.

A will writing tool to let you donate to Comic Relief when you die.

An app called the Napp that let you get sponsored for not using your phone.

And finally an ambitious prototype platform where you could sign in using LinkedIn and get matched with Comic Relief causes that fit your skills - you could then get your friends to sponsor you to volunteer at them, hence fundeer. The website took payments and everything. It was pretty cool.

I think that behind all these projects was a desire to help the charities explore some ideas from the world of startups and digital business that don’t always get airtime in 3rd sector orgs.

We had an explicit focus on pace and delivery. We tried to use new technology to broaden our reach and lower costs. We allowed ourselves the freedom to make mistakes and fail. We tried to build in financial sustainability to our projects and finally we hoped to ensure that we had a route to scale - the distribution systems could take growth, and, ideally, the ventures were ‘backable’ by investors.

Did it work?

I don’t know! Sorry. No one has done any follow up research as far as I’m aware.

Certainly a lot of people who took part learnt a lot, and as far as I know three of the projects are still going some capacity, which is an amazing hit rate.

So, what would I have done differently?

First, we didn’t make real businesses. As in, separate legal structures. This meant we couldn’t incentivise the team with equity, and had no way of raising any external equity of debt finance.

Second, we didn’t setup any follow on funding, so it all had to come from the parent charity and their funders which massively skewed the focus of the projects to matching internal goals.

These things are obviously closely connected.

The big thing though, I think on reflection, was that we focused too much on the methods from the world of startups and not enough on the real context in which they operate. By method I mean the ways of developing products, doing research, building teams. We did this pretty well.

But the context of startups is really this - money. ‘Startups’, in inverted commas, are businesses with very high growth potential, that can achieve multi million or billon dollar exits within fiver year investment cycles. This pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, and the huge inpourings of capital that come with it, is what drives the most ambitious entrepreneurs and investors to create services that scales to hundreds of millions of users very fast.

Here are some of the companies that I’m talking about. And I’d argue, and their PRs would agree with me, that these firms are pursuing social missions as much as commercial goals - taking cars off the road, connecting strangers, providing healthcare.

So, I’ve come up with two ways the 3rd sector could learn from all this.

First, one option is to try this experiment again, but make the context even more like ‘startup land’.

The sector could setup some kind of pooled ‘venture charity’ fund to invest in social, digital business with high growth potential and the money to invest across the whole company life cycle - seed, to series A and beyond. Maybe make a few funds to get competition going. Basically Sidekick School 2.0 on steroids. Its not a bad idea.

Or, my preferred option, don’t do that and just use the context that is already there

There’s a huge, global, sophisticated capital market out there now for investing in startups.

Set your best people free to work on projects that make money, use technology and fulfil your missions by creating real spin outs and then raising money on commercial terms to scale them. There’s a lot of investors looking for projects and people worth believing in who can help you grow, fast. Get out there and meet them!

—

At the event, I got asked a good question:

’Can charity workers be entrepreneurial?’

Here’s my (approximate) answer.

_’Of course! There are huge number of entrepreneurial people working in charities all over the world. I don’t think that’s the question. The question is, can charity leaders be investors? That’s more complex. I’d say generally not, as the way trustee boards are setup and the restrictions on investments and profits makes it super hard for charities to act like investors.

That’s why I made the point about ‘go to the context’. There’s a huge amount of entrepreneurial capital out there looking for smart people with big ideas that will make money and do good. Go and connect them with the entrepreneurs in your organisations.’_

—

If you’d like to talk to me about any of this stuff, the best bet is to tweet me! Thanks for reading.